We are updating this website. Please stand by.

Balancing Act: Memphis Flyer April 1999

Larry Edwards walks a fine line between absurdity and seriousness.

by Cory Dugan

When Larry Edwards came to Memphis 20 years ago, he was painting handsome pictures of stately homes of the sort that line the better streets of Midtown. There was an odd bleakness to those pictures, something vaguely precautionary about the lifeless, manicured architecture that saved them (barely) from blandness. Edwards stated later that, after years of standing outside those dignified houses at a respectful distance, he finally decided to peek in the windows. The result was probably the most dramatic and shocking shift in style and subject in the quaint little history of Memphis art.

The cool observer of exterior facades was suddenly the chronicler of sordid inner desires and their oft-violent consequences. From swirling, oil-paint orgies of dismembered, um, well, members to somber-hued, perspectival allegories that illustrated the side of human nature that makes it less than human, Edwards’ art showed us the nightmare underneath the surface of everyday life.

Nightmares imply dreams and, in art, dreams imply surrealism. And in this body of Edwards’ work, the classic elements of surrealist imagery are at their most obvious. Surrealism is, of course, a school of aesthetic thought that was virtually exhausted half a century ago and most of its practitioners today are stunted adolescents. But there must be exceptions and Edwards is one.

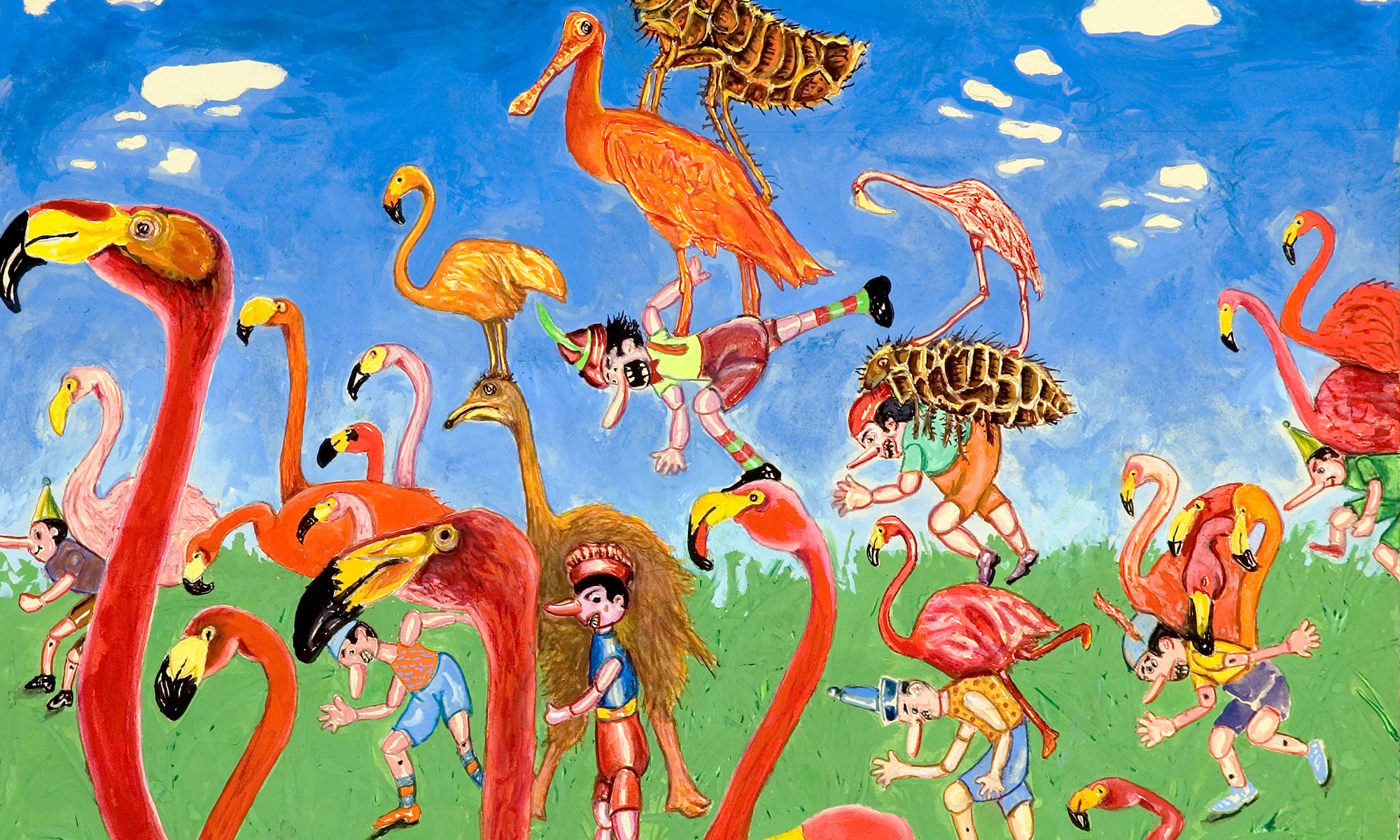

If one describes paintings like Edwards’ The Fall in the Garden (tiny male figures falling from the sky into a jungle of giant irises) or Doubts and Fears at 3:00 AM (two seated male figures facing one another, one with the head of a flamingo, surrounded by giant ants and bats and ghostly puttis with death’s heads), it’s hard to deny that they sound silly. And, in lesser hands, hands with no sense of humor or delight in irony, they would be.

Most of the paintings here fall into two broad categories: the “garden” paintings and the “water” paintings. In the former, beasts lurk among the irises — bugs and ants and hippos and alligators and lions and even ghosts threaten the hapless gardener, whose only recourse is using garden tools in self-defense. (Obviously Edwards, who retired in 1997 from a distinguished career as an educator and university administrator, doesn’t find puttering in the yard quite the Zen-retiree experience that it’s cracked up to be.)

In the “water” paintings, Edwards turns his attention to creatures of the wetter realms — sharks, alligators again, turtles, and fish. Humans don’t fare well in these pictures. A human head slowly sinks among a colorful school of fish in Aquarium Floater, another head hangs in a condom-shaped net above circling sharks in Moroccan Dream, and a swimmer makes a tasty snack in Incident in the Shark Tank. In these works and in the garden paintings, the implied moral to Edwards’ fables seems to be man’s latter-day inability to fit into nature.

Aside from Edwards’ obvious classical skills as a painter and draftsman, the main visual element one notices in this exhibit is a remarkable (and heretofore unnoticed) sense of pattern. Whether the design element is flowers or fish or the stripes in a sandal or carousel horse, these paintings literally dance with color and ornament, aside from and removed from their content.

All said and done, three paintings stand out in the eyes of this viewer, employing and exhibiting the best of Edwards’ various skills in style and subject. False Prophets in the Armor of God is a particularly telling allegory-slash-satire for this particularly embarrassing turn-of-the-century/millennium. Armored figures with the faces of pigs and hawks stand guard around an altarpiece which depicts an upside-down crucifixion; above them dangles a net filled with human skulls. From the bombing of Belgrade to the alleged cleansing of Kosovo, from Belfast to Bethlehem, from abortion to impeachment, this painting is a harsh and fitting tribute to the self-righteous everywhere. The term “religious right” never looked so oxymoronic.

Abandoned Carousel is an odd bit of poetry in Edwards’ library of images. Beneath an eerie green-and-yellow glow, carousel horses take their liberty from their rotating track — zebras and unicorns and plain old multicolored horses. Some of the liberated equines seem lively, while others collapse as if fatally impaled by their carousel poles. It’s an unusually frank but lyrical allegory on the topic of freedom and its consequences.

In Dangerous Balance in the Public Baths, a pair of men in suits, one with a flamingo head and the other with the head of a stork, attempt to negotiate their way across an indoor pool on stilts. The image is innately ridiculous; the irony is delicious, as thick and as smooth as butter spread liberally on the paper. It seems almost a comment on the exhibit itself: In these paintings, even more so than before, Edwards maintains that dangerous balance of the title, that dizzy stilt-walk between absurdity and seriousness. Falling occasionally but falling with grace (if not from it). Larry Edwards can indeed waltz in public with long wooden sticks, be they on his feet or in his hands.

Reprinted by permission.